Ecosystems All Around Us

In simple terms, Scientists described ecosystems as a community of living organisms and nonliving components of their environment, interacting as a system. Usual descriptions describe ecological processes, like the nitrogen cycle, biomes, communities, populations until the concept becomes nearly incomprehensible for most of us. My first understanding of an ecosystem came from a graduate course using the first edition of Robert Ricklefs Ecology in 1974, a foundation text in its eighth printing that broke new intellectual ground for most aspiring wildlife biologists at the time.

But I left graduate school still mystified by the concept, as though I understood it intellectually but not intuitively. Years later, my experience brought a more intuitive understanding in much the same way my son Joe Niles learned calculus and Bayesian modeling to understand trends in options trading. For me, I grasped an intuitive knowledge of ecosystems from my work on the north coast of Brazil in two very different ways.

A finely balanced ecosystem

Several years ago, I organized a fateful trip to northern Brazil to study the coast habitat for shorebirds. The work attempted to understand the unique ecosystem just east of the mouth of the Amazon using remote imagery ground-truthed with on-the-ground surveys. When seen from the air, intertidal mud and sand flats scalloped Magrove into long peninsulas. The ecologically rich region of equatorial Brazil presents an ecological wonderland of rare indigenous species with seasonally large portions of shorebirds that breed in North America. We traveled the area for two years and endured hardship few tourists ever encounter in Brazil, and for a good reason. The area tests human endurance.

I say fateful because, in the first year, our rented 50 ft foot catamaran meant to ferry us to the many inaccessible survey sites sunk in 55 feet of water 8 miles at sea just as we began the journey. At the moment of truth, when the Captain ran out of the cabin yelling ” this boat is sinking” but in Portuguese, leaving us curious and puzzled, at that moment we learned that one of the two liferafts wouldn’t inflate. At the same time, the single outboard bobbed with transom of the deflated zodiac, both sodden and useless.

Fortunately, no one drowned, and we pressed on from land, traveling hard-packed and potholed clay roads to some of the most remote Atlantic coast communities in the hemisphere. But that was only the start. Boats had to take us to even more remote communities following labyrinth waterways that snaked through vast Mangrove Forests. We lived for a few days in small villages composed of shacks on stilts with metal roofs. The residents made an entire life off the sea, surviving with few amenities like fluorescent lights and TVs powered by a community generator at night. The Federal agencies ICM-Bio and CEMAVA protect much of the area by including it in the RESEX reserve system, giving indigenous communities legal rights to resources.

The laws also provide the communities in our study area legal rights, but many town leaders are unaware of them. In any case, they make pennies off the dollars that their catch would eventually bring to city markets. Most of the value ends up in the pockets of the owner class, bankers, politicians, and the rest in a corruption familiar to all rural people in Brazil and the US.

Our team met with community leaders to discuss a complaint about international fleets of fishing ships stealing fish from the reserve that the villagers depend upon for their own livelihoods

Maranhao lies squarely on the equator, so the heat and rain make miserable conditions so awful you dream of clean water and cold showers where you can cool down and freely let the water touch your mouth. Unfortunately, the water is foul and more precious than you might think with all the rain. Poverty makes all the hardships worse, and bitter choices face the people living here. Roads with car size potholes lace the large cities of Sao Luis in Maranhao and Belem in Para, slowing traffic and making ETA’s a guessing game. The contaminated water strikes down tourists and residents alike, despite the Montezuma revenge myth. Bad water substantially decreases the economic value of the country and the two states we surveyed, Para and Maranhao, rank among Brazil’s most affected. The stench of untreated sewage pervades many places, including the many roadside cafes that often only provided open pits as bathrooms. Taxes rob most commerce as corruption, large and small, consumes the more significant part of the public wealth. The infrastructure shows it.

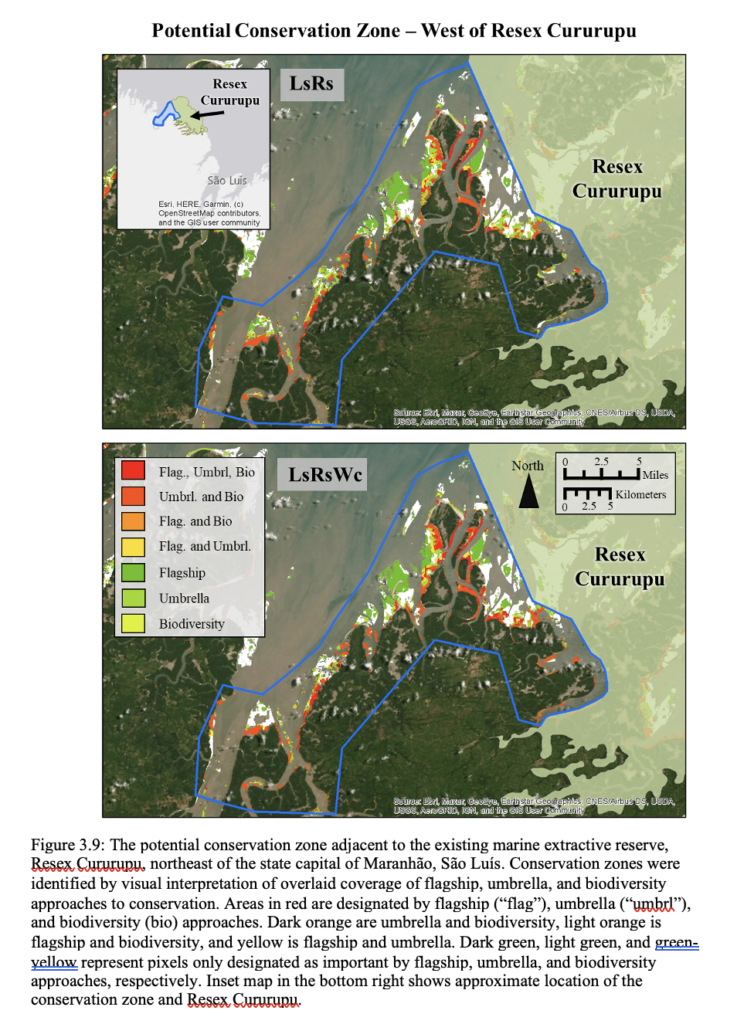

Our survey project ultimately proved successful. We completed all our ground surveys against extraordinary odds, and ultimately Dan Merchant, a Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers, used the data to produce a fine thesis. It told a scientific version of what brought us to the place. Hundreds of thousands of migratory shorebirds make the intertidal mangroves, beach, and the mud and sand flats their winter home, including red knots, oystercatchers, and whimbrels. Dan found that saving the best of places from human use and exploitation starts with the most endangered species, but the wider needs of all birds must define the boundaries of any new protected areas. In other words, the places where red knots occur should guide a manager’s choice of location and the needs of all species, including those using other habitats, like whimbrels or willets, define the boundaries of the reserve. The data will provide the foundation for our next effort – to share the results with Brazilians in Portuguese and English and help them embrace the new technology that Dan’s work represents.

From: Remote Sensing, Modeling, and Management of Migratory Shorebird Habitat in Northern Brazil

By Daniel Macy Merchant

Not because we have the wisdom to share. Far from it, the wildlife biologists of Brazil are among the bravest and knowledgeable in the world. One of our team, Laura xxx just arrived from the Amazon region where gunfights met government land managers trying to stop illegal cutting and mining, No, our value came from the data collected in the field and from satellites that provide layers of information that can be manipulated to emphasize the features that are most interesting for the viewer. For example, a regulator might want to know something very different from a land manager. Dan and his thesis chair, Rick Lathrop head of Rutgers CRSSA Lab, created a digital treasure of information that would be an object of envy in the US.

Data does not fully describe this magic place though. The place challenges nearly all the time while it also beguiles you with the promise of paradise. The sun drops quickly at the equator and evenings distract away all the hardship: the lulling cries of seabirds, the warm and stiff tradewinds off the sea keeping biting bugs at bay, the scent of lush mangroves mixed with salty sea spray, always the promise of paradise. With miles of wild beaches devoid of any humans or any means of rescue, intertidal flats of mud that can swallow a person and hold them, the always dark and impenetrable mangroves with small and large animals that bite sting, or burrow human flesh. The hardships and risk fit like a blindfold obscuring the complex ecological fabric that binds all.

Yet our relentless search for birds in all the places we visited, ultimately provided a faint perception of interconnection like a faint star only visible when looking away. It’s an invisible network connecting all, like an organic nervous system of life interacting without any outside influence but the sea, the air, and the rivers of nutrients emptying the rain-drenched and lush wet and dry forests. You can’t hear an ecosystem, but it speaks with the tangle of bird song in the morning, the rush of water over a parched mudflat bristling with crabs, the wind whistling through the boats rigging and consumed in the dark and tangled mangroves alive with animals mostly unseen. Science proves it interconnected, but the biologist walks away feeling the connection, the timelessness and as with all things, the meaninglessness to all but the observer. The world cannot survive without it.

Looking Inward: an ecosystem of my own

In this way, I could think of ecosystems as ethereal, but reality gave me a personal understanding. I suffered serious bouts of intestinal difficulty, bronchitis, and pneumonia. In one godforsaken town, sickness forced me to a hospital with the help of David Santos of the University of Belem. When I entered, I briefly weighed the choice of risk, a room full of sick rural Brazilians or no treatment for an affliction that was draining this old man’s fluids. Thank the heavens the hospital defied the surroundings, and the staff provided the best of care. Yet I got sick again the following year while staying in an island community with no infrastructure, ubiquitous pigs, and other animals, including a pet oystercatcher. The plane ride home was both risk and relief.

Thus began a four-year health care mystery that left the best of pulmonary, rheumatoid, and infectious disease specialists baffled. I had a smoker’s cough but did not smoke. Skin lesions erupted unpredictably and refused to be abate with usual eczema ointments. Tests showed extraordinary levels of white blood cells and an off-the-chart autoimmune response, but I had no autoimmune illness. For some reason, I had developed late-onset asthma called eosinophilic asthma, which occurs in many older folks for many reasons, including parasites. My autoimmune system stood at DEFCON 5 but for no discernible reason despite years of observation from this professional observer. The cause even eluded my family doctor, Loir Talbot, the best general practitioner I have ever met.

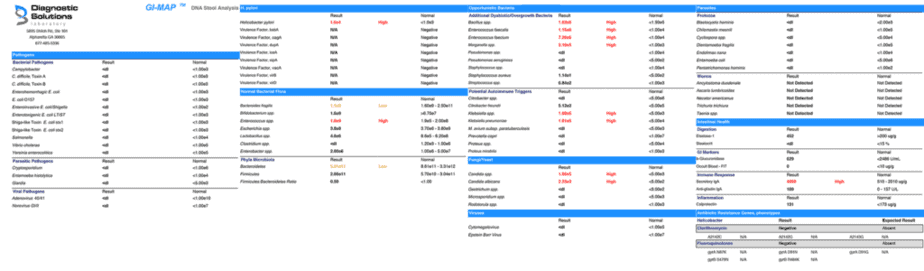

My cousin, Holly Niles, an integrative nutritionist, found that the cause came from inside my body. With a sort of inverted remote sensing of my gut called a GI map by Diagnostic Solutions. The test provides a list of the many species of bacterial flora in my digestive system and measures numbers with normal ranges. The test also provides information on potential opportunistic bacteria, viruses, parasites, fungi that flourish within an unbalanced system.

My test reflected a gut inundated with antibiotics and a diet that fostered harmful candida Albicans and out of proportion bacteria that can cause many assorted problems like my own. A recent NY Times article verified much of Holly’s assessment by relating gut health to many of the problems I suffered and diet as the primary method of addressing it.

I learned that of the thousands of species of bacteria that normally inhabit a person’s gut, mine were overwhelmed by a few bad actors that flourished with all the microscopic carnage brought on by the regular use of antibiotics. This may have resulted from the multiple bouts of a variety of antibiotics necessary to combat the diseases infecting me in Northern Brazil. It didn’t help that I had Lyme disease many times while working on Bald Eagles but also including a more recent infection found in the course of my gut testing. The antibiotics crashed my gut ecosystem, wrecking the biome of life that existed in harmony for most of my 69 years. My understanding of the ecosystem soon became very personal. Holly provided probiotic supplements and a diet emphasizing vegetables and fruits, something akin to a Mediterranean or Paleo diet. The changes in diet and supplements seem like ecosystem management, not for wildlife for my life.

Delaware Bay – an ecosystem out of balance

Ecosystems defy widespread embrace because they cannot find a way into our daily experience, and yet as I found out, they affect all parts of our lives, starting from the inside out. My experience in Brazil and my gut help me put my home ecosystem, Delaware Bay, in perspective.

Delaware Bay resists glorification; it’s no Yellowstone with a grand biome of big animals relying on a well-balanced range or the Gulf of St Lawrence at Saguenay, where marine mammals bask in a rich upwelling of edible aquatic life. Mandy and I regularly visit both places and love them for their bounty and beauty. These ecosystems sing their qualities to all visitors, sometimes raw and frightening, sometimes gentle and spiritual. The Delaware Bay also speaks to me but with a spirit strangled by a history of misuse that continues today.

Intertidal marsh provides the lifeblood of the Bay ecosystem. It’s one of the largest on the Atlantic Coast, but it struggles to resist the rising waters from climate change while still recovering from the damage wrought by centuries of exploitive farming. The horseshoe crab, whose eggs provide one of the bay’s primary sources of productivity, also remains unrecovered after a damaging overharvest over 20 years ago. The eggs from a recovered crab population, five times the current number, could fuel the recovery of fisheries in the bay. Still, agencies find no value in ecosystem productivity as none recognize the bay’s ecosystem as worthy of focus. Fishers kill about 3/4 of a million adult horseshoe crabs every year. At the same time, multinational blood merchants drain up to half the blood of over half a million, needlessly killing hundreds of thousands. They take valuable biochemical LAL from the crab’s blood, making over half a billion dollars while doing nothing for conservation except shower money on greenwashing conservation groups like ERDG. A synthetic exists, but companies and the US Food and Drug Administration impede widespread adoption. Altogether over a million crabs die every year from Delaware Bay and agencies scratch their heads, wondering why numbers won’t increase.

This video was shot in 1986 by NJN TV although the voice-over is mostly incorrect, the video itself is vivid proof of the largess created by horseshoe crabs before fishers overharvested them.

The crabs can lay eggs on Bayshore beaches and marsh in unimaginable densities. In 1986 horseshoe crabs would bury over 200,000 eggs in every square meter of beach. At those densities, beaches fill up, and eggs spill onto the surface and into the sea. Long windrows of horseshoe crab eggs create a natural spectacle of birds and fish devouring eggs just as they commence laying eggs themselves.

We lost most of this spectacle with ill-advised management by agencies that will not embrace the ecosystem’s productivity as part of their mission. This waste has to change.

President Biden’s climate change initiatives aim squarely at restoring American ecosystems as a significant part of reducing greenhouse gases through carbon sequestration. We can restore Delaware Bay’s ecosystem with strong regulations like NJ’s moratorium on bait harvests or adopting synthetic RFC and requiring multinational blood merchants to mitigate any crabs killed by their bleeding practices.

More can be done to fulfill the enormous promise of the bay created by the massive purchase of bay marsh and beach as public land over the last 50 years. Agencies and concerned citizens should stop thinking of abundant species, like menhaden, herring, shad, and eels, to name a few, as worthless unless some corporation makes money from them. Millions of pounds of menhaden go to cat food. Fishers use eels for bait and take their young called glass eels to sell overseas market as a delicacy. Old dams and dikes restrict anadromous fish like herring from reaching spawning grounds. These abuses are unforced errors that the public could change if they demanded it of the politicians that now only respond to the corporations that fund their campaigns.

In the meantime, the bay survives if only on a diet that leaves it suffering “idiopathic” resource failures, a debilitated patient in need of our help. But regardless of its afflictions, the bay will blossom once again this spring. Soon Arctic nesting shorebirds will make a heroic journey from places south, arriving hungry for horseshoe crab eggs. Horseshoe crabs will once again fill beaches and lay their eggs. More people care every year. Ultimately their wishes will prevail.