As our shorebird work reaches a climax, we surveyed what is likely the highest number of birds observed in the Bay for this year. Our entire team devoted May 23 to counting shorebirds, while Bill Pitts from NJ Fish and Wildlife joined Kat Christie from Delaware Fish and Wildlife to conduct an aerial count. Stephanie Feigin, Humphrey Sitters, and I conducted a boat count from Fortescue to Bidwell Creek. We counted 25,614 red knots, 13953 ruddy turnstones, and 16016 sanderlings on the NJ coastline. The count was within a few hundred birds for each species compared to our last count, suggesting that most birds that came early stayed.

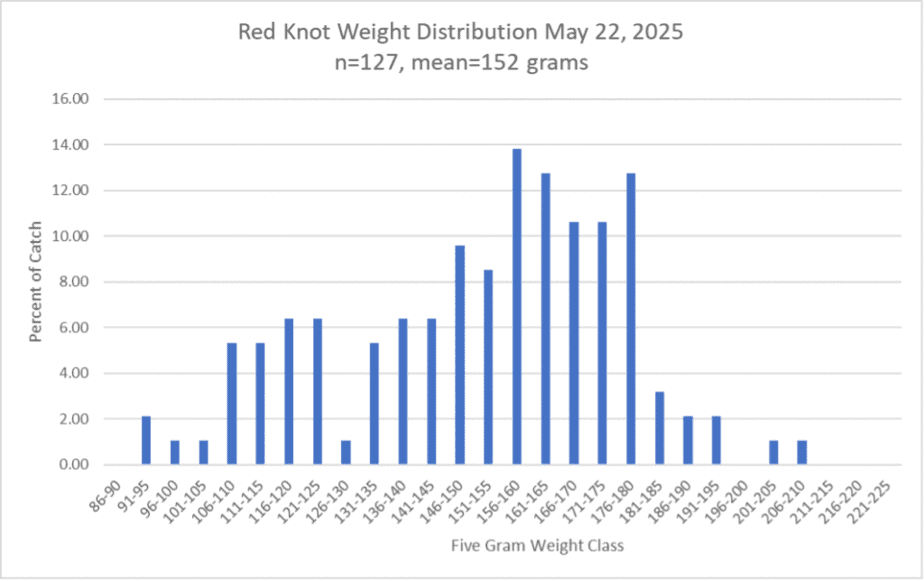

We made several catches in this period, showing birds gaining weight and getting close to the goal weight of 180 grams as seen in the chart below. It also shows a smaller group of late-arriving knots, some weighing less than 100 grams. The fat-free weight of red knots is 125 grams, so these birds burned muscle to reach Delaware Bay.

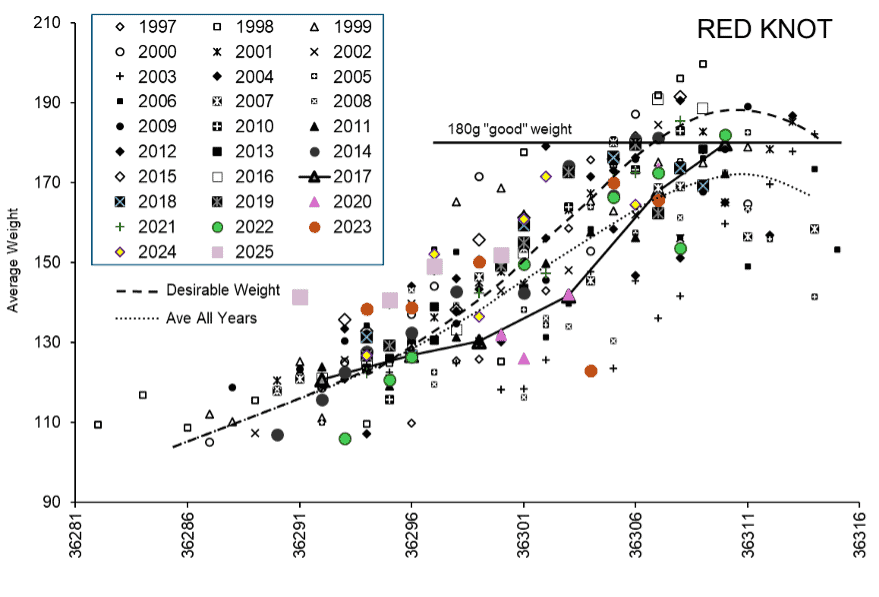

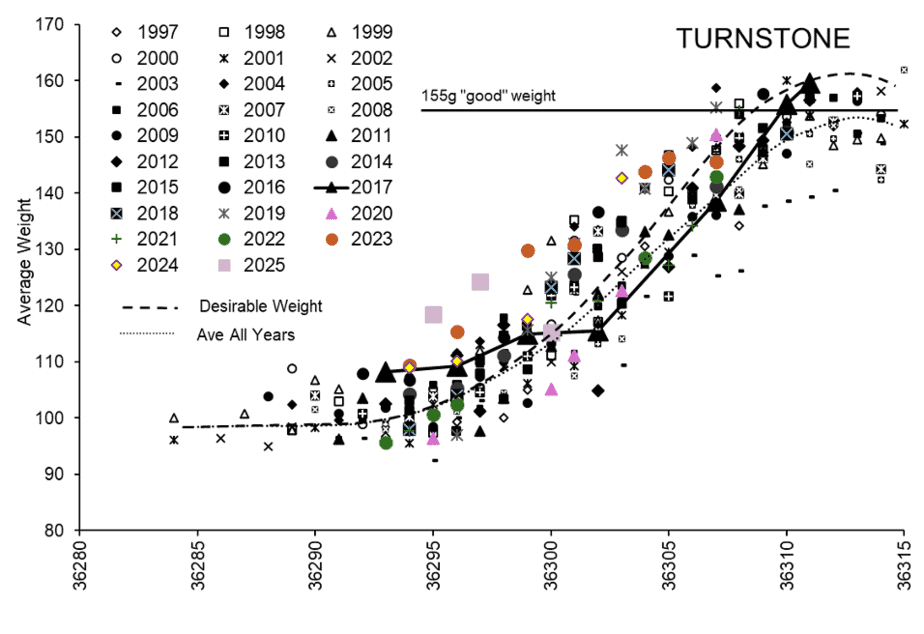

The progress towards that goal weight slowed this week because the horseshoe crab spawn virtually shut down during a 4-day windstorm from the west. West winds blow a long way across the bay, creating big short-duration waves that overturn spawning crabs when they break on the NJ bayshore. The concurrent cold snap that brought nighttime temperatures to near the lower threshold for spawning also stopped crabs from spawning. The birds bore the brunt of the lack of crabs, as seen in the second chart, which shows the average weights of our canon net catches. Our previous catches of red knots and Turnstones showed above-average progress, but our latest showed knots barely gaining weight, while ruddy turnstone weight decreased a bit. We can’t control the weather to make this better, but killing fewer crabs for thier valuable blood despite a readily available synthetic and the senseless use of crabs as bait to catch depleted whelk and eel populations would increase the numbers of crabs spawning so even a cold snap wouldn’t deprive the birds of eggs.

Red knot weights by weight category. The goal of our project is to help birds reach the weight necessary for a productive and safe flight to the Arctic. Chart by S. Feigin

This busy graph plots the average weights of all the catches made since 1997. The 2025 average catch weights showed above-average weights, but our last catch showed slowed progress.

Ruddy Turnstone weight in our third catch actually decreased as new birds arrived and existing birds couldnt find enough eggs.Chart by S. Feigin

These bay-wide surveys remind us of something we tend to forget. Six shorebird species come to the bay to gain weight before moving on to their next stop, Hudson Bay’s little brother, James Bay. Some species arrive early, like short-billed dowitchers, least sandpipers, and dunlin. Others, such as sanderlings, semipalmated sandpipers, ruddy turnstones, and red knots, come a bit later, more closely tuned to the horseshoe crab spawn. Each species has varying migration distances, so they arrive at different times depending on when they start moving north and how often they stop along the way. For the red knot, we know a lot more about its wintering areas because we have been studying it intensively for decades, and now, with satellite transmitters, we understand much about their moment-to-moment movements.

Shortbilled Dowitchers, dunlin, semipalmated sandpipers on a sod bank near Egg Island.

But for the most part, we know much less about the other species, and it has hurt them. Take sanderlings, for example. They winter as far north as NJ and as far south as Argentina. They are the ubiquitous sandpiper written about by so many authors, because they occur throughout the East Coast. They are also abundant, with estimates of more than 300,000 on the East Coast. When agencies consider protection or research, the sanderling is often a low priority.

But here is the thing. Sanderlings, like nearly all the species, have as complicated a migration as red knots. They winter as far south as Tierra del Fuego and on both South American coasts, with good numbers in Peru and Chile. When Delaware Bay was overharvested in the 2000s, the focus was on red knots because of their dramatic migration journey, and the long-distance birds from Tierra Del Fuego took the biggest hit, dropping from 65,000 to 10,000 in only a few years. But sanderlings very likely took the same hit, with very little recognition. Each species has a similar story, because all shorebirds are rapidly declining in numbers. The red knot is a sort of flagship species that can represent all shorebirds. The people who work to save horseshoe crabs should always remember that Delaware Bay is for all of these species.

A lone sanderling taking advantage of two turnstone fighting as they dig for horseshoe crab eggs

Unfortunately, the agencies only focus on the red knot. Take, for example, the Adaptive Resource Management (ARM) model. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission uses this framework to determine the quota for killing horseshoe crabs, but it only considers the impact on the red knot. They measure the number of knots on the coasts, and if that does not change, they consider their job done. They know nothing of the other species, and care almost as little. But we on the bay know better. The bay is home to many species, and we are responsible for all of them.

This graph show the results of the Canadian maritime shorebird survey conducted every year. It shows nearly all shorebird species declining including all of the species coming through delaware bay. Graph by Paul Smith

Members of Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River ( CU) continued to serve our team dinners each night of our campaign. The cooks are gracious and supportive of our work, providing the team with both emotional and gastronomic support. Jane and Pete Galetto, Ferne Detweiler, cooked a delicious turkey dinner in honor of our many members from other countries. Sharry Masarek and her husband, Paul, provided freshly made desserts that our team devoured like red knots on a pile of eggs. We missed Ferne’s partner Dian Shivers, who passed recently. Both have come to feed our voracious crew for years, and Dian would often describe the lost culture of hardscrabble bayshore communities when fish and shellfish were abundant. We appreciated Ferne coming this year despite her loss.

2024 Thanksgiving Dinner with Jane Peter Galetto, Wendy and Dian and Fern Photo by Gwen Binsfeld

During our frequent bay recces, we meet Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ shorebird stewards who help visitors understand the reason for the beach access restriction and educate them along the way. Speaking for the birds, crabs and our team we thank you.

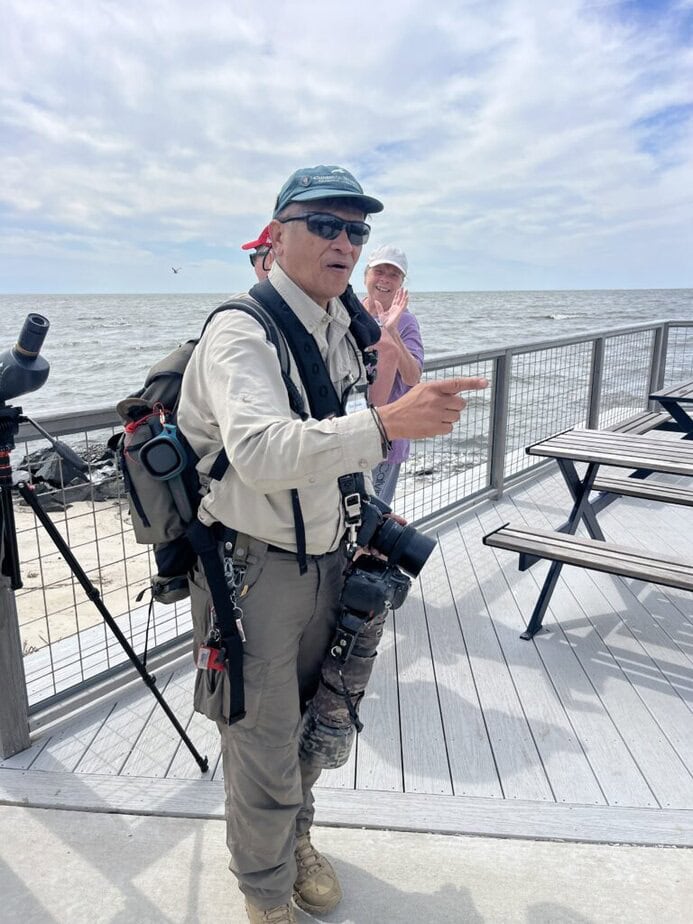

Shorebird Steward Dom Manolo

Shorebird Stewards ( and professors ) Jenny Issacs and Tina Carnacchio.

Shorebird stewards Sheryl and Dan Alexander