A small portion of the 22,000 knots seen on Cooks Beach

Through a mist of fog and rain, we counted 20,000 red knots on May 14 on the beaches between Reed Beach South and Baycove Beach, less than a ½ mile distant. At once, we watched 12,000 knots flying in tight formation, all birds that could only have just arrived. We had not seen a flock of this size in years, so the sight was a joy for all of us. After a thorough recce of the lower beaches, Humphrey, Stephanie and I estimated over 22,000 knots, 2,000 ruddy turnstones, and a small number of sanderlings and short-billed dowitchers. The knot number is a puzzle. Last year, a bay-wide count conducted on the May 22 turned up only 12,000 knots. But in 2022, we counted 22,000 knots, so why did the number go down and then up?

Atlantic State Marine Fish Commission statisticians dispute our counts, even though they are mostly verified by their own three-day estimates. For example, last year, when we saw only 12,000, the Atlantic States Marine Fish Commission statisticians, biologists with limited field experience but outsized power to justify killing crabs, estimated 43,000 knots. The ASMFC dismisses our numbers because they are “too variable,” as though the difference is a consequence of poor fieldwork, even though they are being conducted by biologists with decades of experience estimating numbers all over the world. But their arrogance clouds the true meaning of the two estimates.

I spoke of this once with Environment Canada’s Dr. Paul Smith, an intelligent and accomplished statistician as well as an intrepid Arctic field biologist. He said, “The difference between the two numbers is telling us something,” and he is right. The agency biologists are basing their numbers on the number of birds resighted with unique ID leg flags, and they are very likely estimating the entire red knot population of the East Coast. They see no need to separate birds that come to the bay and only stay for a few days from those birds that come to the bay to build up weight. Our number represents the birds that mostly stay and gain weight. In other words, one tells us the status of red knots, while the other reflects the status of the Delaware Bay stopover.

1700 red knots flying over cooks creek inlet nj. Photo by Charles Duncan

This is a very important distinction. When numbers go up and down, there is a reason; there are not enough crabs to fill the beach with eggs and keep birds in the bay for as long as they need to gain weight. Yet the ASMFC uses the higher number, even though their remit is not to estimate the number in the red knot population, but to assess the health of the stopover. Focusing on the former numbers helps them maintain the killing of horseshoe crabs.

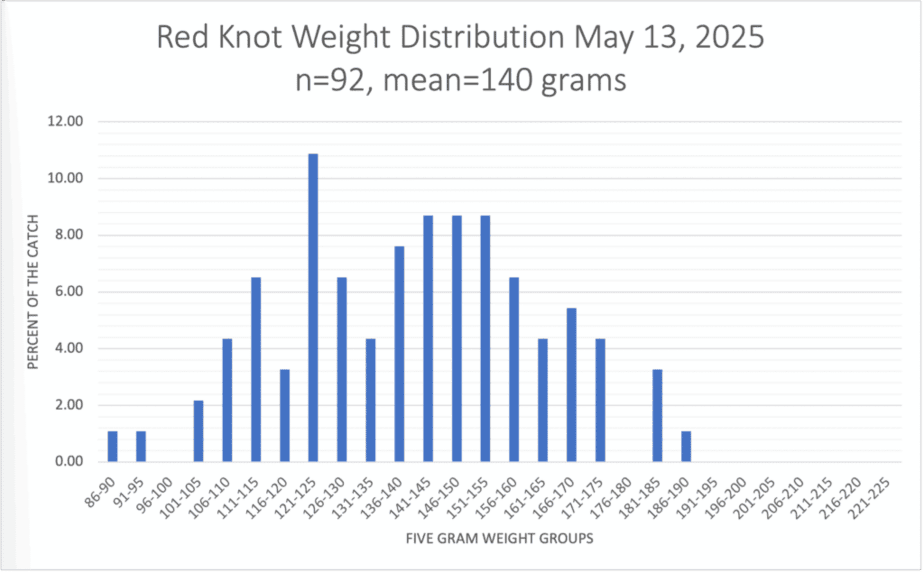

We made our first catch on May 13, the first day of our fieldwork. Even though we were blessed with thousands of red knots, the catch wasn’t easy. We were faced with an abundance of riches: where should we set the net when we could set it in many different places? After a shift in location and many frustrations, we caught 94 knots. The weight distribution seen on the chart created by Stephanie showed a wide range of weights, probably the widest in our 28 years. One poor soul measured only 84 grams, a deadly weight for knots, so she was lucky to reach the bay and its bounty of eggs. In the same catch we caught birds that weighed a hefty 194 grams, a number we rarely see anymore, especially not at the beginning of the season. It’s a puzzle we will solve by the end of this season.

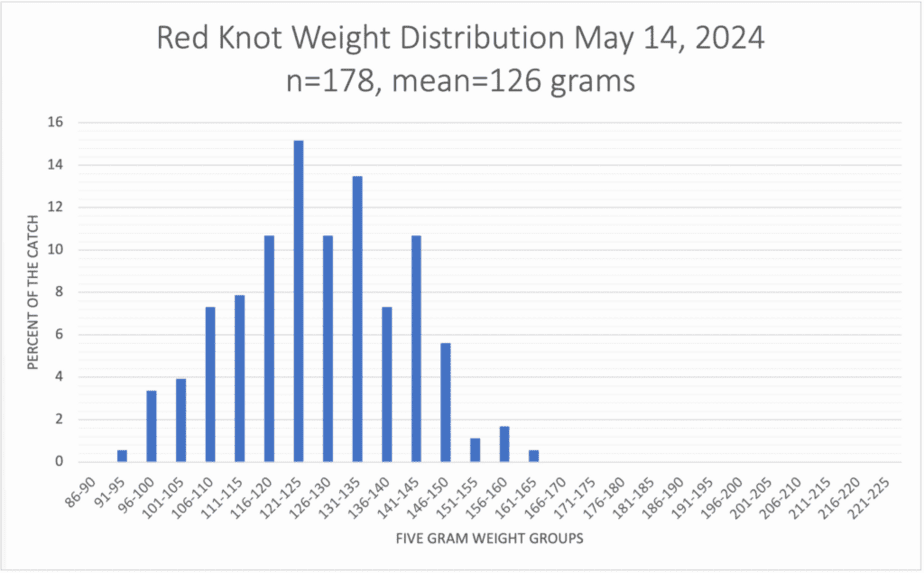

Above are two charts of weght classes of red knots caught on May 13 compared to a weight historgram from last year. They show the much greater range in weights than is usual. first is constructed by

Finally, I would like to thank two more of the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of NJ Stewards protecting our beaches we encountered at Cooks and Kimbles Beach, Erica Garfinkle and Barbara Bennett.

Erica Garfinkle.

Barbara Bennett