This blog focuses on the conservation of wildlife and rural communities that depend upon them. These blogs are meant to help people who care for wildlife and would like to join in the many efforts aimed at improving conditions for wildlife and habitat. Conserving wildlife not only helps animals but rural communities that rely on hunting, fishing, bird watching, and other outdoor sports to create an economy that overcomes the economic burden of living in important ecological places like Delaware Bay.

Feature photo by Stephanie Feigin

previous post

We made a new catch of 8 knots on our last day in the field (Oct 1), bringing the total number of released birds with satellite transmitters to 19, and thus completing this campaign. We were fortunate to find these birds south of the Lagoon inlet, although it is very likely they are the same flock that Antonio discovered before we arrived. The re-discovery of this flock of 120 red knots warrants some attention.

Red knots in flight in Lagoa do Piexe Park Brazil

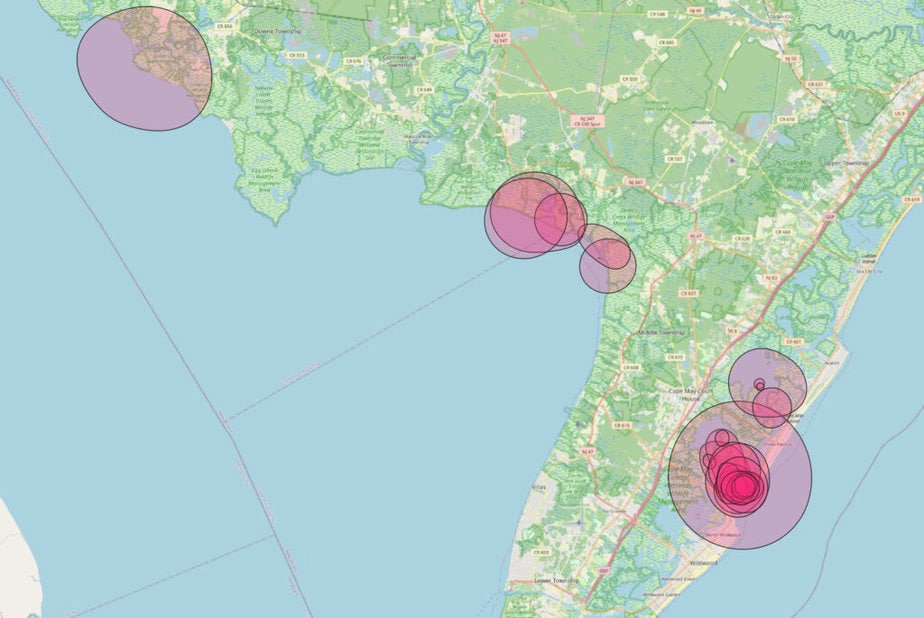

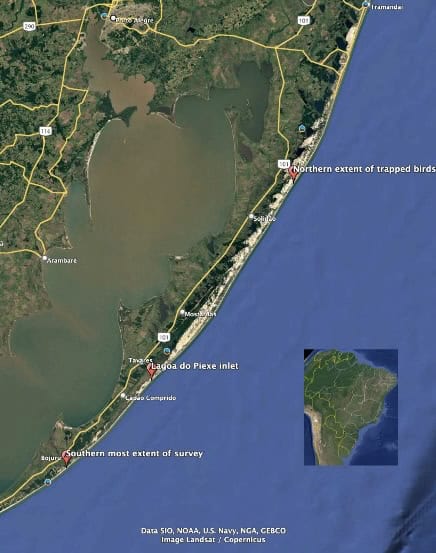

The three sites we trapped and the area we surveyed for red knots

When we first arrived at Lagoa do Peixe National Park, we trapped where the large flock was last seen, the area north of the lagoon inlet. We found only about 30 knots and assumed the rest of the flock had moved south, ultimately to wintering grounds in Tierra del Fuego. We tagged three of these birds, who stayed in LDP, but the others moved to inaccessible sites within the lagoon, or so we thought.

We had to look elsewhere for knots, so when Mateus Haas left with Victoria Becker and William Salvi Kuhn, they volunteered to drive along the beach from Mostardense to Pinhal, 140 km without any river inlets to block their path. They found a new flock of 20 knots about 10 km north of the appropriately named lighthouse Farol da Solidao (lighthouse of solitude) and 70 km from Mostardense. We caught another 8 knots from this flock, but they also disappeared, leaving us with only one option: to go south of the lagoon inlet. However, our expectations were muted, and we lowered our goals for the expedition, assuming no birds were in the area.

Mateus crossing a tidal stream on beach north of Mostardos

We assumed no knots in the Park below the lagoon because none were seen in earlier surveys, although they were weeks ahead of our arrival. Also we saw none there in 2023. But thankfully we were wrong.

When we arrived, we found 120 birds and immediately realized we had miscalculated. In 2022 and 2023, the ocean swell and currents kept the inlet closed with sand. When the inlet closes, it’s a completely natural event that benefits the commercial fishers by helping shrimp multiply, which improves the fishery. However, it also allows gill net fishermen to drive across the inlet and set their nets. It’s still a dangerous crossing, as in 2023 we nearly lost a truck, but the local people know the way across with only small cars.

In 2023 we crossed the inlet several times, but it was treacherous if we strayed from the local people tracks. Here fishermen saw us and came out to help.

But this year was different. The inlet is open, and a deep channel flows from the ocean to the lagoon, preventing any vehicles from riding the southern beach. Knots, who notoriously avoid disturbance, voted with their wings to relocate to the south side. On the first day heading south, after a 2-hour drive, we found over 60 knots. The second day, the entire flock of 120.

Thankfully, this lack of disturbance proved decisive. With over a hundred birds in the flock, we were able to make two more catches that brought our total instrumented birds to 19. And although a very small sample size, the birds told us an interesting story.

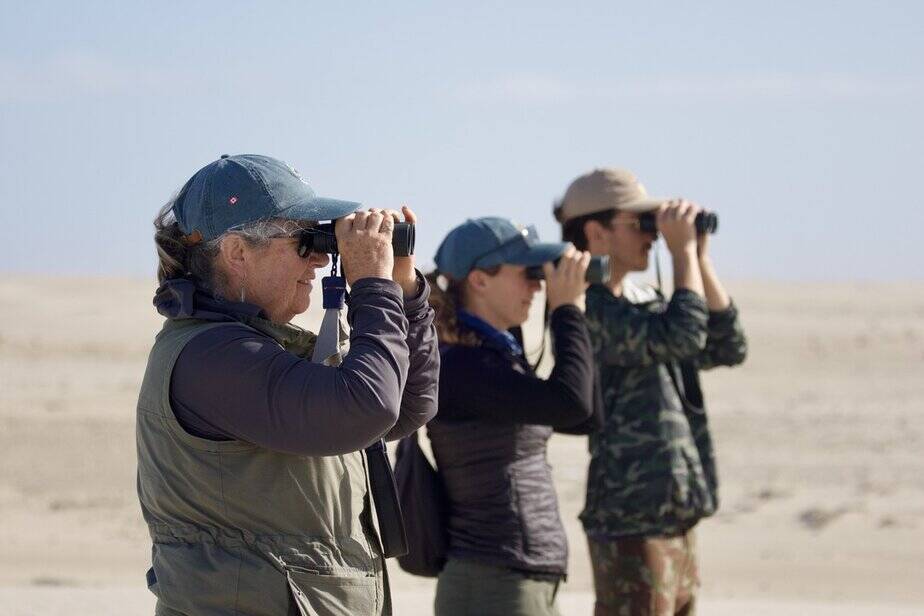

Gwen Binsfeld, Steph Feigin and Francisco Zanella search for knots across the inlet

Stephanie Feigin twinkles knots closer to the net. Twinkling a technical term developed by Clive Minton describes the subtle skill of moving cautious and prone to flight shorebirds closer to the catch area of the cannon net.

Antonio Brum twinkles birds closer to the net

Antonio Brum and Larry Niles holds a bird originally banded in Delaware Bay and recaptured on LDP south of the inlet. The bird was an adult at a fat free weight of 125 grams. I hold a heavy juvenile weighting 150 grams. Photo by Francisco Zanella

Antonio, Douglas Da Silva and Tamires Fogaca Martins sample a red knot for Avian Influenza. The bird was caught on the beach north of the Lighthouse of Solitude. Photo by Francisco Zanella.

The recaptured knot >UP is being measured. All birds are fully measured, weighed sampled for AI and sex determination and finally tagged. This birds was originally banded in Delaware Bay 2012.. Photo by Theo Diehl

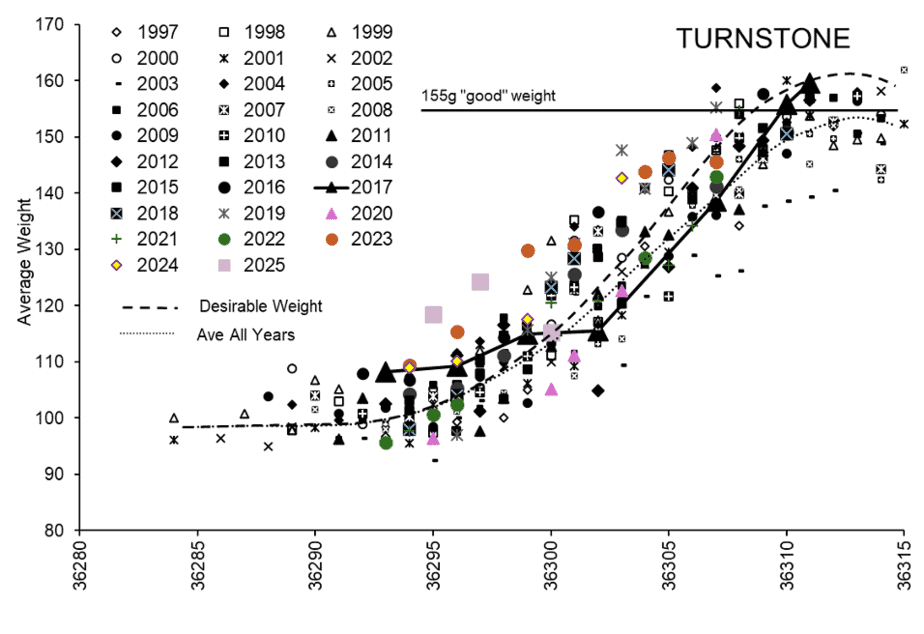

Unlike our earlier catches, where all birds weighed less than 130 grams, a fat-free weight for knots—the second group of knots from the undisturbed south—included birds weighing up to 160 grams. As I explained in my earlier post, weight provides comfort against starvation but increases the risk of predation. However, this late group mixed everything up. Adults were at both high and low weights, as were the other ages, so they gained some weight but not enough to reduce predator avoidance, maintaining a good balance.

Like the other catches all had yet to molt their flight feathers. Adults displayed feathers worn from years of flying, while juveniles had crisp, new feathers grown only a few months ago in their Arctic breeding area. Of particular interest were the modestly worn feathers of subadults or young birds from the previous nesting season. These birds stay in their wintering area during their first year, then join adults heading north in their second year, or so we believe. As juveniles, they get their feathers in early July, but as subadults, they molt later than juveniles but earlier than adults.

The wings of three knots caught on LDP south of the inlet. The bird on the lower right is a juvenile, born this year in the Arctic. Her black sub-terminal wing coverts confirm the lack of wear on the feather and yellow legs. The birds on the top is an adult showing wear on feathers grown last year and likely to molt in the wintering area. The bird on the left I judged a sub adult, or a bird born last year.

As an aside, the skill of gleaning this information from feathers is practically a sacred right for aspiring shorebird biologists. I learned this from British shorebird scientists like our beloved Clive Minton or my friend Humphrey Sitters. In Britain, it is a highly honored skill to discern the life stage of a bird through subtle changes in feather wear and molt. We saw all three groups in both catches, and distinguishing them will help us interpret the movements we observe from the transmitters.

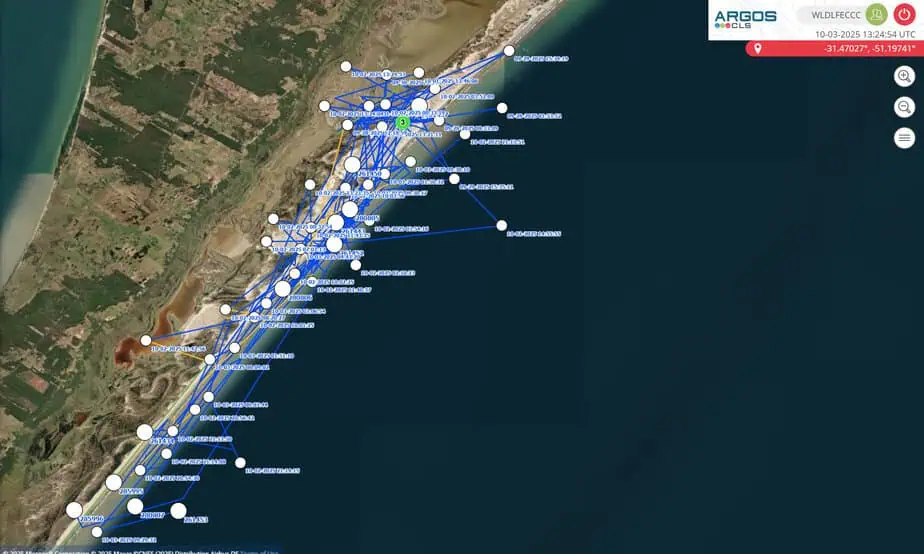

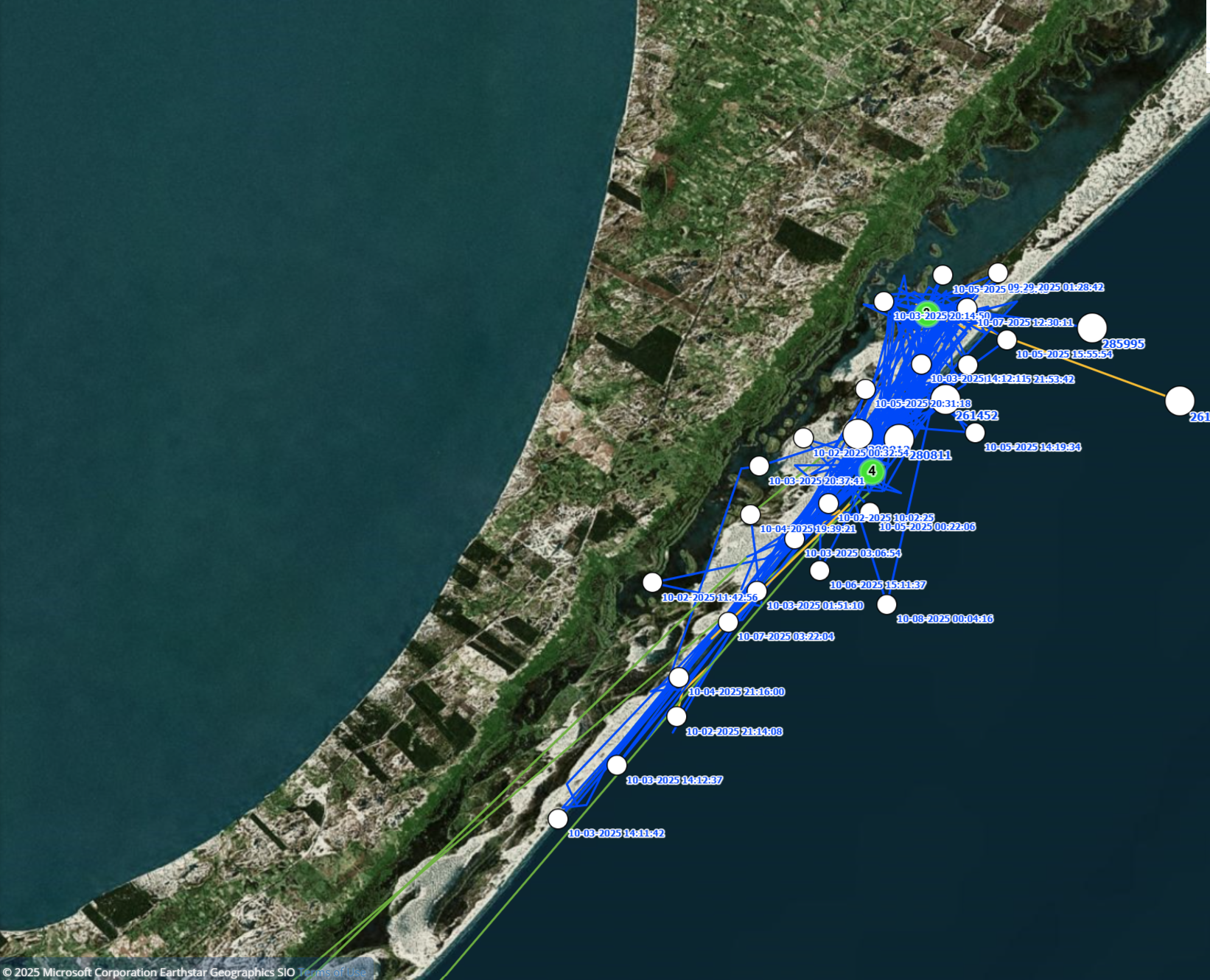

We left Lagoa do Peixe on Oct 2 and arrived home on October 4, and I am writing now on Oct 8. The success of our work can be seen in this one image of the tracks from the Sunbird transmitters we attached to the knots. They transmit regularly, so we will get a clear picture of their movement and stopovers all the way to the wintering area. As I write, one bird has already arrived in Bahia Lomas, and we will know very important information from this. The area is about to undergo significant change, with ambitious plans for wind power and other new infrastructure. These data will help defend the knots. And it will be for some time because our team has been successful with attachments that last.

This map summarizes all the locations of red knots in the LDP until Oct 2.

This maps shows knots tagged with satellite transmitters leaving LDP. Two are already in Tierra del Fuego

So, our project was a success despite all the difficulties we faced. The success belongs to the many people who took part in the work, and I will list the team again. From North America, Stephanie Feigin, Theo Diehl, and Gwen Binsfeld; from Brazil Antônio Coimbra de Brum, Roger da Silva, Francisco Roberta Zanella, and Dan Gonzalez. Mateus Haas, Victoria Becker, Will Salvi Kuhn, and Luisa Matuella Fra helped during the first week, and Tamires Fogaca Martins and Douglas da Silva in the second. We thank all of our team for their quick learning and hard work, enduring more net sets per day than any team has before. Antonio’s major professor Uwe Horst Schulz visited for a few days and helped us work through some problems. We are very thankful to the folks at ASA and especially the owner Julia de Brum Marantes, who reopened the cabins just for us to have a safe place to anchor our expedition. We thank the Lagoa do Peixe National Park and ICMBio staff for helping us and giving us permission to do the work.

Uwe Shultze, Antonio’s PHD advisor at Unisinos walks the beach of LDP

We held a final dinner after returning from the field. Antonio’s family joined team members at a traditional Brazilian restaurant Churrascaria Cultura Gaúcha. From left to right Douglass and his wife Bruna K. Reichert and their son Murilo Ribeiro ( running around the resturant) Stephanie Feigin, Gwen Binsfeld, Larry Niles, Edison Kufner, (Husband) Alcedina Brum (sister), Santa Olíbia Brum (mother), Theo Diehl,Roger and his wife Larissa C. Martins , and Antonio Bru

Churrascaria Cultura Gaúcha

We stayed on a 400 acre farm known as Aldeia Santuario das Aves or ASA. The owners, Julia and her father Renato Callares de Brum Marantes (with thier farm hand Caubi Gomes de Lima) repurposed the farm to continue raising sheep and horses but devoting much of the land to a refuge for wildlife. This photo was taken in 2023 before Senhor Renato‘s death earlier this year. ASA had been closed since but Julia reopened ASA for our team. We are very grateful.

We also thank Christian Friis of the Canadian Wildlife Service, Paul Smith of Environment Canada, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation for support.