Dear Team

The previous day (May 19), we conducted our first baywide survey because the only red knots we could find in the bay were at Norbury’s Landing, Moores Beach, and Fortescue, totaling less than 2000 red knots and even fewer ruddy turnstones. In 2019 we had about 20,000 knots and 15,000 ruddy turnstones at the same time of the season. In 2020 the number fell considerably because cold water delayed the meager horseshoe crab spawn. The red knot population fell like a stone in 2021 to 6800. Were we on track for another terrible year for this stopover? We started our boat survey in Fortescue, heading southeast along the Bayshore to Bidwell Creek, a journey of about 25 miles.

We found an additional 7000 knots, the majority in peregrine-free Egg Island. The site is the largest contiguous intertidal marsh in the bay and the most distant from the mainland and is an area free from where NJ Fish and Wildlife continues to manage nesting Peregrines.

An adult bald eagle watches while shorebirds feed on horseshoe crab eggs at Egg Island NJ

Water temperature has again delayed the horseshoe crab spawn. The last full moon on May 16 only modestly increased egg availability for the birds because the temperature has only today climbed above the threshold water temperature for spawning of around 59 degrees. Egg densities will climb, but as of yesterday, many of the sites still show low densities.

The combination of modest egg densities and the peregrines have left most of the main beaches, from Reeds to Pierce, empty of shorebirds. For the last two days, we have been searching for birds to catch, going to places where the resighting team found birds on the previous day or even the previous few hours, only to find the sites depopulated presumably by peregrines, despite some areas having visible horseshoe crab eggs on the beach. The boat count suggests we will see more birds than last year, but our hopes are dimming for a return to the numbers seen 2019,

A Peregrine falcon at Moore’s beach NJ eating a migratory shorebird

So what is happening to the Delaware Bay stopover? At this point, only halfway into the three-week season, prognostications would be guesses. But our data suggest several trends for our beleaguered stopover. First, the water temperature reduced the horseshoe crab spawn that should have been robust. The agencies will pass this off as the impact of climate change, but the truth is more complicated. If we were not killing 1 million Delaware Bay-origin crabs every year and if we had double the number of crabs as before the overharvest, the egg numbers would probably be tripled. So in a cold year, instead of 5000 eggs/sq meter, we would have 15,000 eggs/sq meter or more. Even in the best of conditions, most beaches peak at 10,000 egg/sq meter.

The peregrines add to the problem. When 30,000 knots stopped over in Delaware and similar numbers of the other species, a few peregrine pairs and their young from the previous breeding season could cause trouble, but the number of birds overcame the threat. But reduced numbers and more isolated birds in smaller flocks give the determined predator a much better chance of killing birds. Even the most junior wildlife observer will know shorebirds gaining large amounts of fat will be sitting ducks for a non-native predator, a fact that seems to elude agency biologists.

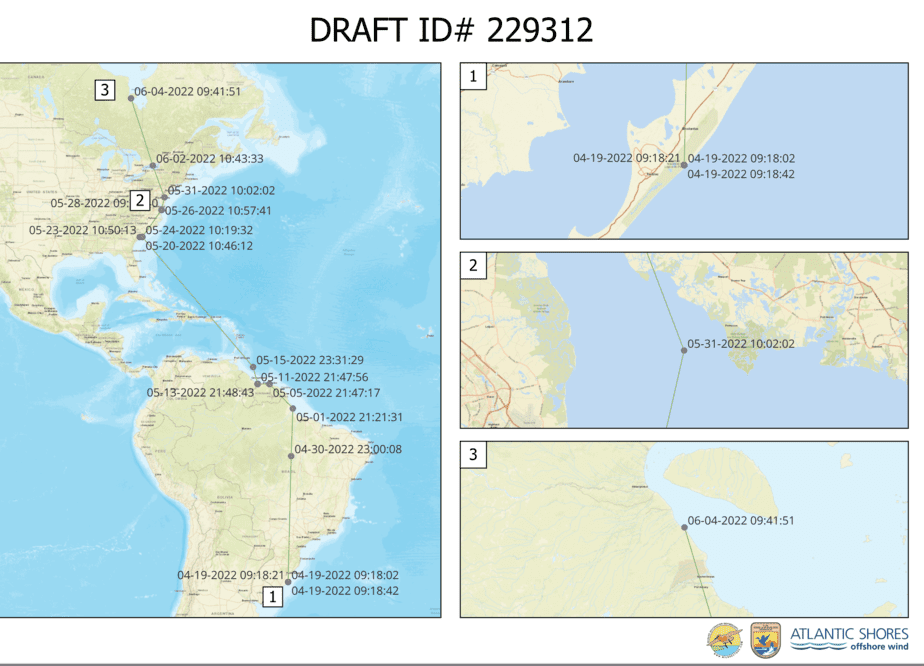

We are now reaping the results of the agency-led double assault on the Delaware Bay stopover. Our red knots tagged with satellite transmitters suggest knots, and probably other species are finding other resources and bypassing Delaware Bay. We might record them for a few days, but sadly they may no longer rely on the bay to get to the Arctic. Worse, many may have died because they could no longer rely on the bay stopover. The red knots with satellite tags attached in South Carolina and Lagoa do Piexe, Brazil, show the impact. Two of the three birds arriving made surprising moves. The red knot from Brazil went to South Carolina instead of Delaware Bay, and of the two birds tagged in South Carolina, one came to the bay, the other skipped Delaware Bay and went to Jamaica Bay. ( see the maps below)

This red knot with a pinpoint satellite transmitter attached in Lagoa de Piexe Brazil flew to South Carolina then to Virginia before arriving in Delaware Bay. It stayed only a few days in Delaware Bay before moving on to Canadian Arctic. The bird used other stopovers to get the weight it needed and not Delaware Bay, a sign the bay is no longer dependable, a critical value of the Delaware Bay stopover lost because agencies allow the killing of too many horseshoe crabs.

Today we do the first baywide count, so we will see if the number equal last year’s low of 6800 or the 2019 high of 30,000.

The birds that do come are well cared for by our volunteer stewards like Shoanne Courtade, the steward at Fortescue. She quickly came to our crowd at Norbury’s Landing when we arrived to assess conditions for trapping, fully prepared to chase us away. We talked to her for a few minutes, and she inspired all of us with her heartfelt appreciation of crabs and birds. Despite the problems, we went home reassured because people like Shoanne, the crabs, and birds would prevail.

Shoanne Courtade, the shorebird steward at Fortescue Beach NJ.